A Q&A with A Call to Men Trainer Jeff Matsushita

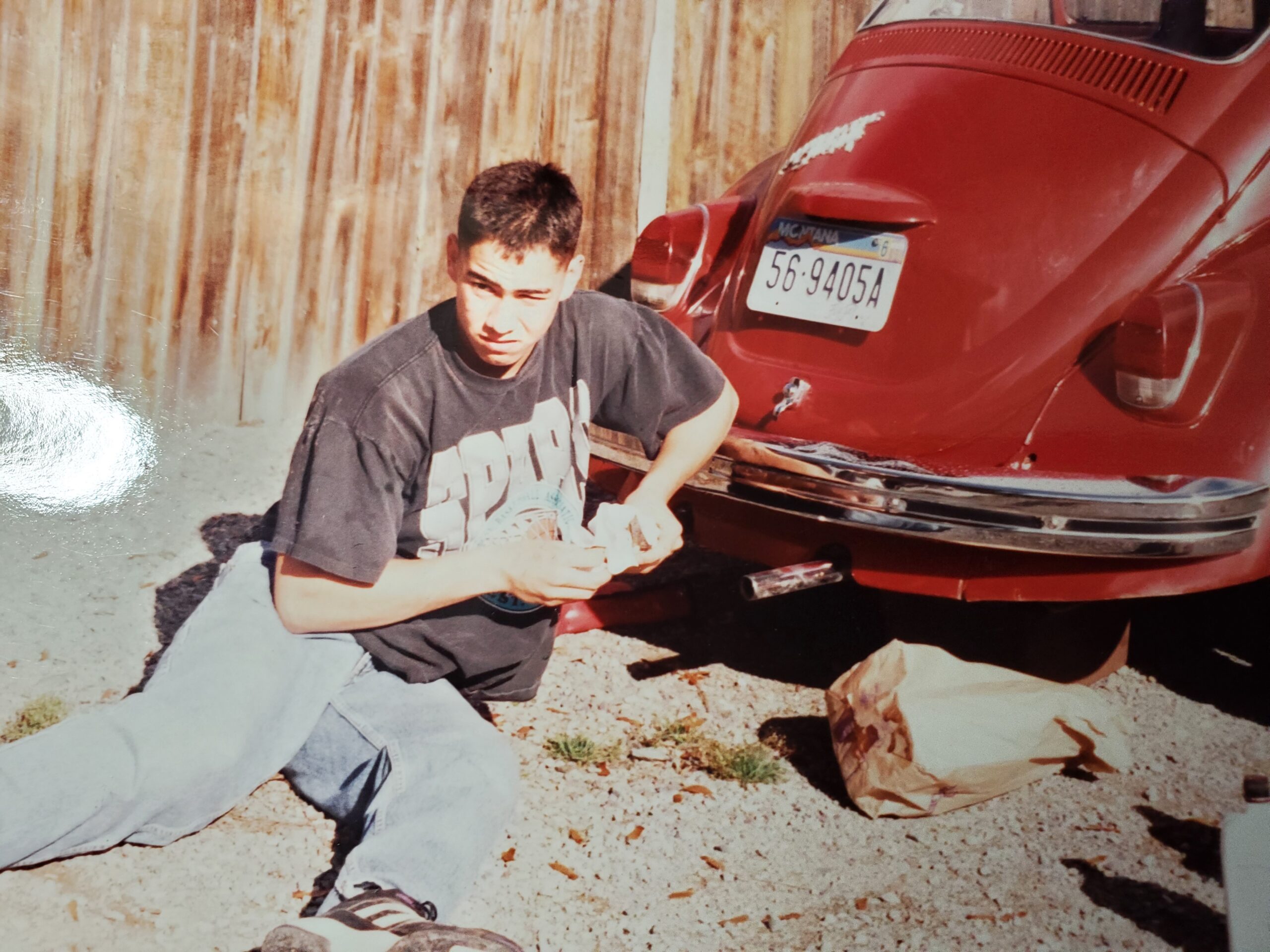

Jeff Matsushita had very little connection to his Asian heritage. A biracial Japanese man, Jeff grew up in Troy, Montana, a small town of roughly 900 (mostly white) residents. That proximity to whiteness is what led Jeff to be assimilated into “American” culture by his father. The only time they experienced Japanese culture was through the occasional dishes offered at his grandfather’s end of the long dinner table—away from the traditional American dishes placed by his white mother’s family who sat on the opposite side.

Being so far removed from what others might say is the typical Asian American Pacific Islander experience, Jeff was hesitant at first to speak to AAPI Heritage Month. But it’s his uniqueness, and his work as an A Call to Men trainer, that makes his experience compelling. That’s why we asked him to share his experience with us as we reflect on his heritage and how it links to manhood and his mental health.

How were you raised to view masculinity as an Asian man?

In our house, stoicism was the expectation. Never brag or boast. No emotional outbursts when non-family members were present. Stifle victories. Accept what is given. Yet, it was in conflict with my rowdy, boisterous friends (mostly white middle-class kids) whose parents were also teachers.

Ironically, I was drawn to the Black Panthers and hip-hop culture. The Panthers’ image, their clothing, their insistence to resistance, and overall portrayal of Black masculinity was wonderfully divergent from the version of masculinity my Japanese father modeled. Instead, he self-deprecated and laughed at the racist jokes directed towards us. He kept his head down, insisted on not causing division. Without saying it, my dad was leading me to believe that if we just kept our heads down, didn’t make a ruckus, we would be ok.

Data shows that the AAPI community is reluctant to seek out professional mental health services. In your experience, why do you think that is?

My dad changed my trajectory when he dialed the Montana Domestic Violence Coalition hotline, seeking resources for his mental health. It was the mid-1980s and he told me he was seeing a therapist to work on his “anger Issues,” which could be interpreted as code for depression. When I asked what made him dial the number, he shared that he knew he was going to eventually hurt my mom and/or me. He modeled vulnerability by reaching out for someone to talk to. Eventually I even saw the same therapist, this time in the early 1990s. But for all the benefits the sessions provided, we never discussed them outside of our home. I never heard my dad discuss it with his friends, coaches, or football players. So I kept my sessions under wraps, too.

What are some ways that you destress personally? And what tips would you offer to others?

When discussing trauma, Roshi Norma Ryuko Kaweloku Wong said, “if we don’t heal our wounds from trauma, we will bleed all over those we love.” This statement jump-started my practice of meditation in 2020. I had dabbled during our staff meetings with seated meditation, practicing how to breathe, and even practicing Tai Chi. But during the COVID-19 pandemic, I was encouraged to turn towards meditation again from my therapist and our Roshi. I use a free app on my phone and practice meditation three-to-five times per week. It helps me to be present, grounded, and prepare for the day or workshop that is coming my way. I started with a three-minute meditation for kids and have progressed into 10- to 15-minute meditations. It’s free, quick, and I usually feel better.

What’s one thing that you know now that you wish you knew back then, and how do practice #HealthyManhood with your two children?

My dad only talked to me once about puberty and sex and sat me down for the other talk about racism. Whereas my dad’s talks were polluted with anti-Blackness, my talk with our two multiracial kids links our liberation to that of others. There is no mention of the harassers’ best intentions or our kids’ responsibility to make sure the harassers are “ok.” No description of how to shuffle through it. My job as their parent is to learn, listen, and grow alongside them. We read books and stories about the people who struggled, endured, and resisted so we could thrive. Sure I sprinkle them with some wisdom dust now and again, but my work is to heal so we can thrive. When we know better, we do better.