Bringing Black Trans and Queer Activism to the Forefront

When we think about the way American history is told – from when Africans were enslaved to the civil rights era and beyond – the common thread in all of the narratives we’re taught is the erasure of queerness and the invisibilization of the contributions of queer folx throughout history.

As a Black trans woman, learning the characters that have defined the history of my people has been central to my own journey and identity. And the more I got to know these key players, the more apparent it became just how much of an impact the Black queer community has had on the freedoms and rights that all of us enjoy today. Here is just a handful of the many Black trans and queer folx who have been instrumental in shaping our collective history.

Frances Thompson – A Voice for the Unheard

When I first started looking into the archives to uncover the hidden players in Black trans and queer history, I found the story of Frances Thompson – the first Black transgender woman to testify before Congress. Thompson was a formerly enslaved trans woman who lived in Memphis, Tennessee. On May 1, 1866 – during an event known as “The Memphis Massacre” – white Irish police officers asked a group of folks consisting of Black men, women, children, and Black Union Army veterans to disperse in the midst of a street party. The crowd refused to leave, and police attempted to arrest the veterans. There was a growing rumor among the white townsfolk that this refusal to disperse was the beginning of an uprising. Groups of white vigilantes formed and randomly began shooting Black men, women, and children. This went on for 36 hours. It is estimated that hundreds of Black people were victims of assaults and robberies. Four Black churches, four Black schools, and 91 other dwellings were destroyed in arson attacks. Forty-six Black people were killed, and countless women were raped. Frances Thompson and her cisgender roommate, Lucy Smith, were among those raped by the white terrorists.

When I first started looking into the archives to uncover the hidden players in Black trans and queer history, I found the story of Frances Thompson – the first Black transgender woman to testify before Congress. Thompson was a formerly enslaved trans woman who lived in Memphis, Tennessee. On May 1, 1866 – during an event known as “The Memphis Massacre” – white Irish police officers asked a group of folks consisting of Black men, women, children, and Black Union Army veterans to disperse in the midst of a street party. The crowd refused to leave, and police attempted to arrest the veterans. There was a growing rumor among the white townsfolk that this refusal to disperse was the beginning of an uprising. Groups of white vigilantes formed and randomly began shooting Black men, women, and children. This went on for 36 hours. It is estimated that hundreds of Black people were victims of assaults and robberies. Four Black churches, four Black schools, and 91 other dwellings were destroyed in arson attacks. Forty-six Black people were killed, and countless women were raped. Frances Thompson and her cisgender roommate, Lucy Smith, were among those raped by the white terrorists.

A Congressional committee was formed to investigate the massacre, and Thompson testified. Thompson would go on to become one of most important figures during that era because of her testimony, which led to the Reconstruction and Enforcement Acts as well as the Fourteenth Amendment – laws which together extended civil rights to Black Americans.

Ten years after the Memphis Massacre, Thompson’s transgender status was exposed when she was arrested on charges of “crossdressing.” Opponents of Reconstruction used her transgender identity to discredit her testimony, cast doubt on whether or not she was raped, and to fight against the newly formed laws. Thompson was sent to prison, forced to detransition, placed on the chain gang with men, and died alone. Despite the oppression she faced, Frances Thompson’s monumental contributions to history are felt to this day. From our modern vantage point, it’s essential that we ask why she has been erased and omitted.

Lucy Hicks Anderson – Marriage Equality Advocate

When we think about marriage equality here in the U.S., most of us think back to June 26, 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court deemed state bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional and legalized it in all fifty states. Most people believe the gay marriage movement started to heat up in the 1980’s and gained momentum in the 2000’s. However, our understanding of this movement is incomplete without going all the way back to the 1930’s to learn about the case of Lucy Hicks Anderson, a socialite, chef, and prohibition-era entrepreneur. Anderson was born in Waddy, Kentucky in 1886. As a young boy, she insisted on wearing dresses to school, and her doctor encouraged her mom to let her live as a female. By age 15, she changed her name to Lucy, left home, and moved to Pecos, Texas. In 1920, she met and married her first husband, Clarence Hicks, and relocated to Oxnard, California.

When we think about marriage equality here in the U.S., most of us think back to June 26, 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court deemed state bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional and legalized it in all fifty states. Most people believe the gay marriage movement started to heat up in the 1980’s and gained momentum in the 2000’s. However, our understanding of this movement is incomplete without going all the way back to the 1930’s to learn about the case of Lucy Hicks Anderson, a socialite, chef, and prohibition-era entrepreneur. Anderson was born in Waddy, Kentucky in 1886. As a young boy, she insisted on wearing dresses to school, and her doctor encouraged her mom to let her live as a female. By age 15, she changed her name to Lucy, left home, and moved to Pecos, Texas. In 1920, she met and married her first husband, Clarence Hicks, and relocated to Oxnard, California.

Anderson worked as a chef, won awards for her cooking, and hosted lavish dinner parties for the wealthy citizens of her town. When she saved up enough money, she opened a boarding house as a front for a brothel. Her good standing in the community made it easier to run her illegal business. She divorced Hicks in 1929, and married Reuben Anderson in 1944.

When there was an outbreak of sexually transmitted infections in her city, folks claimed it originated from Anderson’s business. The female employees were ordered to undergo a physical examination where it was revealed that Lucy was assigned male at birth.

At the time, marriage was only valid between a man and a woman. They invalidated her marriage and arrested Lucy for perjury. She and her husband were tried by the federal government. During her trial Anderson insisted, “I defy any doctor in the world to prove that I am not a woman. I have lived, dressed, acted just what I am, a woman.” She was placed on ten years probation. One year later, they charged her and her husband with fraud because she was receiving financial allotments reserved for wives under the G.I. Bill.

So, when we talk about the history of gay marriage and queer marriage, why are we not starting with Lucy Hicks Anderson? Is this not a marriage rights case? It is essential that we examine history with a critical eye, considering the reasons why our textbooks do not credit her for establishing the foundation for marriage rights. While she may not have won her case, the precedent she set of pushing up against the systems of oppression was groundbreaking. Acknowledging and honoring the contributions of our Black trans ancestors is essential to understanding and learning from our collective history.

Pauli Murray – Pioneer for Equal Rights

One of the most central and impactful people in the advancement of all of our rights as citizens of the United States – not just for Black folks, not just for women – is the inspiring Pauli Murray.

One of the most central and impactful people in the advancement of all of our rights as citizens of the United States – not just for Black folks, not just for women – is the inspiring Pauli Murray.

Born in North Carolina, orphaned, and adopted by her aunt Pauline Fitzgerald, Pauli (born Pauline) was educated by her aunt at a segregated school. Even at a young age, she began individually protesting unjust laws. She refused to get on segregated streetcars, opting instead to walk or ride her bike. She did not go to the movies because she did not want to sit in the balcony. Instead, she became an avid reader. After graduating high school, she worked for a year to earn enough money to attend Hunter College in 1929, where she became one of four Black students in a class of 247.

While in college, Murray began calling herself Pauli. Convinced she was a man in a woman’s body, she tried unsuccessfully for years to obtain hormone therapy. She would wear pants and cut her hair short, but was never able to live as her gender – something that would continue to plague her for the remainder of her life.

She applied to the University of North Carolina to study sociology, but was rejected on the basis of race. Years later, she applied to Harvard Law School for graduate study, but was rejected because of her gender. Murray found herself – an educated Black woman for the time – pushed out of academia because she sat at the intersection of two sources of oppression: her race and her gender. This intersectional oppression (a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw) would have a profound impact on Murray’s life, fueling and informing ideas that would later become pivotal cases in U.S. history. Both Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Thurgood Marshall were heavily influenced by Murray’s work, and many of the ideas that made waves in the legal system at the time originated with Murray.

In March 1940, Murray and a friend traveled through Virginia by bus on their way to North Carolina. They refused to move to a broken seat on the bus, which resulted in their subsequent arrests. The NAACP attempted to use this case to challenge segregation laws, but a judge changed the charge to disorderly conduct to sidestep the challenge.

This was one of the events of Murray’s life which inspired her to attain a law degree from Howard University. During her time there, Murray and fellow students planned sit-ins and picket lines, and managed to integrate two restaurants years before what we traditionally think of as the Civil Rights Era of the 1960’s. Pauli Murray’s early contributions set a foundation for political strategy and passion that would later define the movement.

During one of Murray’s courses at Howard, she argued that the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause should be used to bring down Plessy v. Ferguson. Despite vehement disagreement from her male classmates and determined she was correct, she bet her Professor Spottswood Robinson $10 that Plessy would be overturned within 25 years. Ironically, Robinson kept the paper and referred to it ten years later when he, Thurgood Marshall, and the NAACP were preparing Brown v. Board of Education. As we know, they won that case. What is not widely known is that Pauli’s analysis was the foundation for their successful arguments.

In 1971, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg presented Reed vs. Reed – her first gender equality brief to the U.S. Supreme Court – she credited Pauli Murray for her delineation of the connection between race and gender, and her approach of using the equal protection clause to litigate for gender equality. These were crucial steps that laid a foundation for her case.

It is essential to Black futures everywhere that we understand and acknowledge Murray’s contributions to the rights that we have as women and the rights that we have as Black people.

In our classrooms, we learn about Brown vs. Board of Education. We know about Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her women’s rights project. Why have we not heard about Pauli’s contributions to both movements?

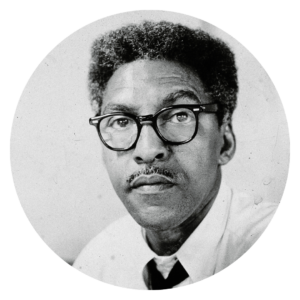

Bayard Rustin – Leader in the Nonviolence Movement

Martin Luther King, Jr. is often who we think of when we picture the nonviolence movement. While he undoubtedly left a lasting legacy and fed the spirit of the movement with his “I Have a Dream” speech, what is often omitted in our history is that the architect of that non-violent organizing strategy was Dr. King’s mentor, Bayard Rustin – a gay, Black male socialist. Rustin organized the whole march on Washington, the non violence approach and ideology, the sit-ins at the diners, and much, much more.

Martin Luther King, Jr. is often who we think of when we picture the nonviolence movement. While he undoubtedly left a lasting legacy and fed the spirit of the movement with his “I Have a Dream” speech, what is often omitted in our history is that the architect of that non-violent organizing strategy was Dr. King’s mentor, Bayard Rustin – a gay, Black male socialist. Rustin organized the whole march on Washington, the non violence approach and ideology, the sit-ins at the diners, and much, much more.

Rustin presided over every aspect of the planning for the March on Washington in 1963 – including a flurry of phone calls, a series of meetings with volunteers, meetings with officers about techniques of non-violent crowd control, all the way down to finding the correct number of first-aid stations and toilets needed for a quarter of a million people. He booked buses, vetted speeches, and ordered food…all while ensuring he remained under the radar.

At the time, being gay was illegal in most states. Ten years prior, Rustin had been charged with a sex crime when he was jailed and registered as a sex offender for having consensual sex with another man. Due to the anti-gay laws and sentiments during this period, his fellow civil rights activists feared they would risk the whole campaign by putting him in charge.

Rustin could not even speak at his own organizing event. Hoover ordered his FBI to gather information about Rustin’s sexuality and past — and delivered it to Strom Thurmond, a white segregationist senator from South Carolina. Just two weeks before the March, Thurmond took to the floor of the Senate, where he denounced Rustin. Efforts to derail the march failed as civil rights leaders rallied behind Rustin. The march went on as planned, and the rest is history. But why don’t we hear Rustin’s name in the narrative about that era?

Preventing Queer Erasure In History & Building a Better Future

The patriarchy centers cisgender, heterosexual men in all these movements. We know women were an often unseen but central force – providing an intersectional lens and political strategy to work towards ending unjust practices – but because of patriarchy, their accomplishments have been erased or diminished. In that same way, queer and trans people and their contributions have also been removed from our collective understanding of the past.

The patriarchy centers cisgender, heterosexual men in all these movements. We know women were an often unseen but central force – providing an intersectional lens and political strategy to work towards ending unjust practices – but because of patriarchy, their accomplishments have been erased or diminished. In that same way, queer and trans people and their contributions have also been removed from our collective understanding of the past.

So when we talk about Black rights, when we talk about women’s rights, when we talk about men’s rights – it is so essential that we center and uplift those forgotten voices. We must commit to undoing the erasure of queer people and women. Those at the margins of the margins have had to chip away at this boulder of hate and oppression. It is important for those in power to recognize that honoring our contributions to history does not take anything away from the contributions men have made to these movements.

We’re at a crossroads as a society right now. People are speaking out against the teaching of accurate American history. They’re openly fighting to erase our stories. We cannot let it happen. We are in this fight together, but we cannot achieve true liberation until those at the margins of the margins are valued as equals.

Moving forward, how do we prevent the erasure of trans, queer, and nonbinary folks in our culture and communities?

- Learn about queer & trans people and queer & trans history. Read memoirs and autobiographies. When searching through archives, be intentional and diligent about finding out who and what is being erased from this narrative.

- Diversity isn’t just about race. If you’re trying to be diverse in hiring practices, diversity is also about gender, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Truly centering and supporting people at the margins of the margins is critical to building more authentic, accepting communities and organizations.

- Give to organizations that are doing the work to end gender and racial violence – whether that means donating your time, money, or influence.

Diamond Stylz (she/her/hers)

A Call to Men Advisory Board Member

(More about me)